WORKPLACES: PAST AND PRESENT | INTERVIEW

Rick Halpern and Maica Gugolati from Workplaces interview Katya Lachowicz on the film Silvertown. Workplaces Past and Present brings together international scholars in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Argentina, Turkey, South Africa, and Bangladesh to investigate, in a collaborative and interdisciplinary way, the past and present of the workplace. It is especially concerned to move across the divides between the global North and South, between different disciplines, and between different methods and orientations. The project draws on a range methodologies and on tools in the digital humanities and social sciences to archive, curate, and disseminate results and findings to audiences of students, scholars, activists, and the general public.

To read the interview and view the film: https://workplaces.omeka.net/exhibits/show/silvertown/interview

Interview with Katya Lachowicz

The docks were formed by the hands of migrant

labourers; they became centres of commerce and later were abandoned.

They became the site of an airport, exchanges of a vertical axis. As the

old factories disappeared, and the towers grew, they were built once

again by the same invisible force. The film's multiple reflections and

intermittent disturbances challenge the pursuit of infinite growth and

hint at the tales of migration, labour and rhetoric that have sustained

it: workers are still creating the city with their hands from the depths

of the underground.

Why is the notion of “hypnosis” important as a leitmotif for this project?

I have a background in both visual art and anthropology. The film set out as an exploration between myself and a sound artist, Clelia Patrono, of the transformation of the London Docklands as a site of de-industrialisation and gentrification. As opposed to a traditional documentary style of ethnography, the work abandons any form of spoken narrative and sets out instead to create a hypnotic palette through visuals and sound. I wanted to experiment with an alternative interpretational framework beyond the written word. Trance-like states take on a liminal perspective, it is the transitional moment within a rite of passage where the participant is shedding one form and becoming something else. The viewer thus is encouraged to partake in a sort of psycho-geographical journey, to feel the change from its material surroundings and sounds, and to understand it not only from the present but perhaps also as a palimpsest of conterminously layered time. I wanted to see whether it would be possible to allow that which was no longer visible (e.g. the absence of the workers who built and managed the docks) to re-emerge through an alternate form (in the work of the present-day construction workers). In this sense it is not only a document of one period of development in the Docklands, but an entirely new space in which the trajectory of capitalism is reflected upon through the Docklands.

Can you expand upon titling the film ‘Silvertown’?

The transformation of the docks represents a shift from the period of industrialisation to financialization in the British economy. The title ‘Silvertown’ hints at both its past and present. Silvertown is a small area just off the Royal Docks, constructed as a later addition to the Docklands between 1855 and 1921 in response to the introduction of larger steamships at the height of British imperialism. The docks became one of the busiest in the world, bringing goods from across the empire. The area Silvertown was named after the S.W. Silver & Company, a rubber factory that moved there in 1852, later developing into a telegraph works that spearheaded the ‘All Red Line,’ laying submarine cables that asserted British rule over its colonies. Very soon Silvertown became the site of a series of manufacturing companies that remained in the area until the development of just-in-time logistics and containerization in the 1960s, making inland ports, factories, and manual dock-work redundant. The port was once the life and butter of the communities whose closely-knit generations lived in the rows of houses around it. Social deprivation led to the abandonment of the area at large, which has increasingly been subject to social cleansing (White & Lee 2020).

Why did you choose the Docklands? What are the main concerns that animate your critical treatment of this site?

My existing body of work often has questioned spatial politics, and the Docklands are a very particular example of that especially with the underground construction of Crossrail, a fast commuter railway line connecting the suburbs with the centre. I initially had taken interest in the great concrete wall surrounding the tracks, which cut across Silvertown breaking the district in two with barely a bridge to cross. A community art project had been devised to decorate the walls, but little interest was expressed in it, so I became intrigued and went to see the situation for myself. The pubs were mostly closed. There was hardly anyone on the street. I knocked on a door and spoke with a couple who had grown up in the area and were now retired. The room shook from the vibrations of the lifting planes in the airport down the road, and they told me about the East End and how you could once hear the honk of the ships in the dock. Generations of families lived there working in the docks and surrounding factories. They were disappointed with the breakdown of the industry and the community that went with it, particularly the lack of prospects for their kids and grandchildren, all of whom had left the area. Initially I thought I would include their narrative in the film, but I was reluctant to make it solely an account of oral history. Instead it was the feeling of absence and loss conveyed in the conversations that guided the shots I later would take. I still have a desire to make a sequel that features the couple alone – however, I see this as an additional piece and perhaps one of many multi-facetted snippets.

What is the relation of the video with its last part? Who, exactly, is “they” in “they all wanna talk”? Why do you mention Allah?

The last part is where the journey reaches a climax, in the midst of birdsong and clouds there are scenes from Hyde Park’s Speaker’s Corner, a famous location for public debate since the 1800s. This is not anywhere near to the Docklands but I decided to use the footage because it conveyed a sense of delirium, loss, and a search for answers to something that felt too large and out of the hands of ordinary people. Speaker’s Corner was historically the place of progressive dreams, where the Suffragettes and other activists would speak. That Sunday when I came to Speaker’s Corner, Muslims and Christians were talking over each other. One preacher remarked, ‘they all want to talk, but they don’t have any answers.’ It was the tyranny of the loudest speaker who would come to dominate the stage, whether they themselves had the answers or not. In the background a man repeated himself that America would start World War 3, and another chanted ‘Allah’ as if to drown the noise around him. Feelings of fear, alienation, righteousness, were all muddled in the cacophony of voices. There was something apocalyptic about the scene, a sense of powerlessness. I remembered the conversation I had with the couple back in Silvertown who told me it was useless to protest because ‘who was listening, the government would do what it wanted anyway.’ I felt this to be very symbolic in the context of Silvertown’s trajectory. The closing shot of the film shows the financial hub Canary Wharf, towering over the flatness of the water in the dock. There is an oddness to the serenity, as if on the cusp of rupture.

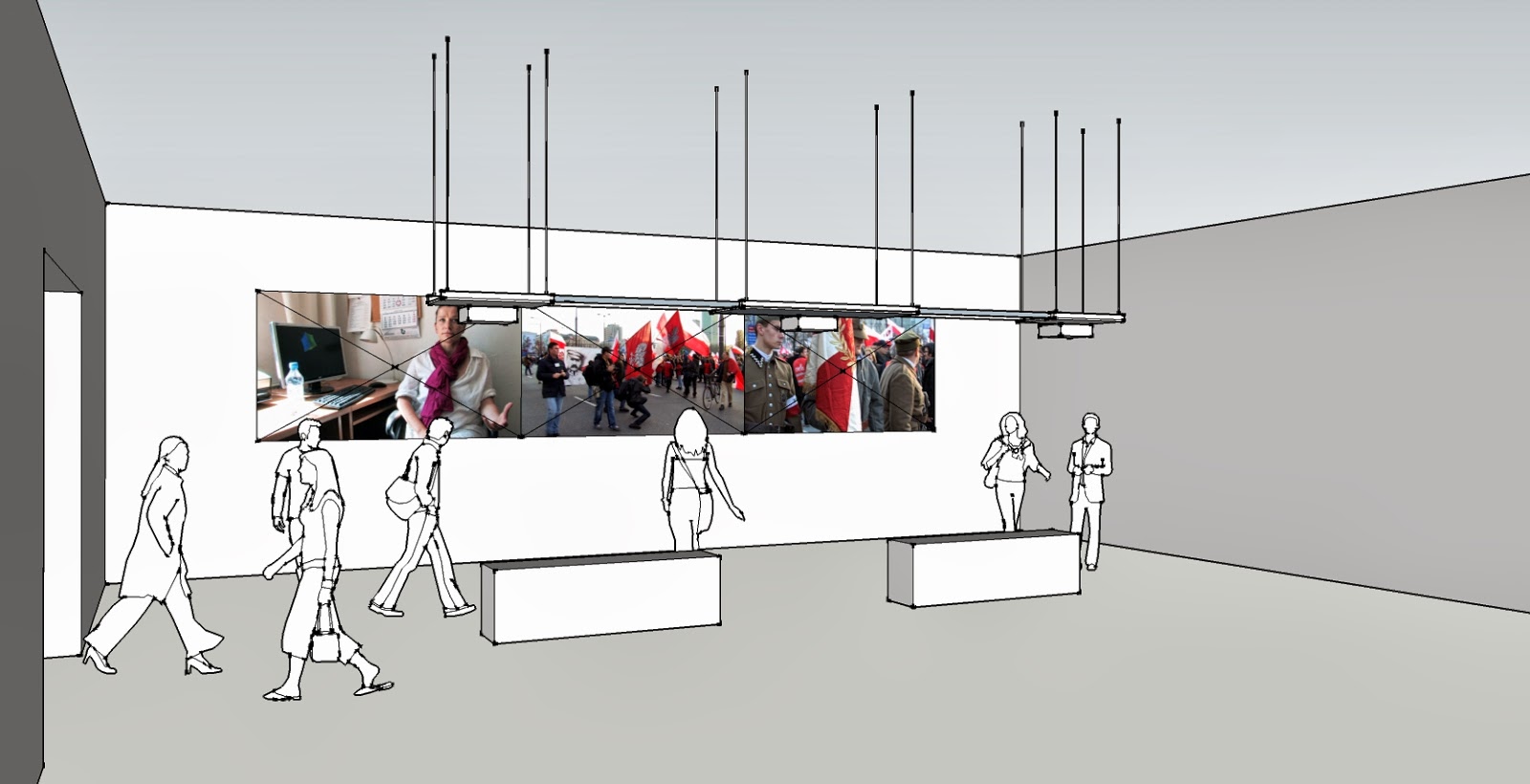

State of the art

Most contemporary academic research based on the Docklands is about this shift from industrialisation to financialisation and what has become of it. Tim Butler (2007) remarks how respondents are ‘very explicit about their lack of concern for social interaction’ (774), and how this is even reflected in the void uniformity of the gentrified architectural landscape as if to echo Margaret Thatcher’s saying ‘there is no such thing as society.’ More recently, Carola Hein discusses docks in the context of global networks and local transitions, resilience, and disaster (2013, 2021). The Docklands are also framed in terms of racial capitalism and the repressed memories of slavery (Legg 2023) as well as the precarious conditions of 19th century dockworkers (Palmer 2003) and union presence (Lovell 1969).

As for films, the derelict Docklands became the backdrop of many action movies, such as Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) where the factories were turned into a Vietnamese city, John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1979) a crime drama of the property and finance boom, or the site of a boat chase in Michael Apted’s James Bond movie The World is not Enough (1999). Derek Jarman also comes to mind, with his film The Last of England (1987) in which the present is shown to brutally collide with the past under Thatcherite neoliberalism.

In terms of visual artists, the docks and waterways are where many have engaged with the material artefacts they have mudlarked from its banks, such as Mark Dion’s Tate Thames Dig (1999) or Cecilia Vicuña’s Brain Forest Quipu (2022). In fact Mark Dion’s cabinet of curiosities has lingered in my subconscious since I first saw it -- the idea of unearthing a small personal token from the past, pulling something out of the dirt. Silvertown in this sense shows quite the opposite, it glistens with the clean opaqueness of the new as progress occupies the territory of that alleged ‘empty’ space. This is what I tried to convey when using the docks as a turning axis of above and underground. You can see many ventilation shafts resembling space missions or loose pieces of ceiling, which feel more like part of an aircraft than a railway. It resonates with Elon Musk’s SpaceX and the insatiability of neo-colonial conquest and extraction.

REFERENCES

Butler, T. (2007) Re-urbanizing London Docklands: Gentrification, Suburbanization or New Urbanism?

Palmer (2003) The Labour Process in the 19th Century Port of London

Some New Perspectives

Hein, Carola (2013). "Port Cities". In Clark, Peter (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 809–827 [821].

Hein 2021 Resilience, Disaster, and Rebuilding in Modern Port Cities

Legg, G (2023) Excavating Racial Capitalism in London's West India Docks

Lees, L. and White, H. (2020), The social

cleansing of London council estates: everyday experiences of

‘accumulative dispossession’, Housing Studies, 35:10, 1701-1722, DOI:

10.1080/02673037.2019.1680814

Lovell, J. (1969) Stevedores and dockers: a study of trade unionism in the Port of London, 1870-1914, Macmillan

.....

Mark Dion’s Tate Thames Dig (1999)

Cecilia Vicuña’s Brain Forest Quipu (2022)

Jarman The Last of England (1987)

The World is not Enough (1999)

The Long Good Friday (1979)

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Comments